Platforms and Ecosystems

In contrast to traditional businesses, companies with digital platforms no longer simply create value themselves, but provide a means for outside entities to provide additional value, and then share the augmented success. In this new model, the platform is more important than the products sold.

The unstoppable advance from digitisation to rapid innovation, based on the fusion of technologies that blur digital, physical and biological norms (often referred to as the Fourth Industrial Revolution) is forcing companies to reconsider how they do business.

Whether a business client or an individual consumer, customers are at the centre of the economy, one in which collaborative innovation, product enhancement and increased customer expectation are central considerations.

New forms of business operating models are needed to respond to this new imperative - the corporate command-and-control organisational structures and the governmental law making processes have barely evolved from an era when decision-makers had the time to study a specific challenge and then develop an appropriate response.

The unpredented pace of change demands a business model which has inbuilt agility to cope, and one which facilitates and actions the corporate learning so essential to adapting to new trading scenarios.

Not only does an organisation's revenue generating ability now depend on the customer experience and the depth and breadth of the relationship with the customer cohort, but the valuation of a company and its market capitalisation is rapidly shifting to being dominated by a business model which is based on a digital platform and an ecosystem.

In this new model, the platform is more important than the products or services sold. In contrast to traditional business operational practices, companies with platforms no longer simply create value themselves, but provide a means for outside entities to provide additional value, and then take a share of this augmented success.

Company size or age is no impediment to grasping this new opportunity. Traditional organisations are, with the relevant understanding, with Exec committment and with guidance, just as likely to succeed as born-digital startups.

Participation results in value generation

Corporate success has often been judged on scalable, efficient growth, where the aim is always to sell more, and at a better margin. In contrast, the digital economy platform and ecosystem approach is one in which the number of participants in the community is a more reliable indicator of success. The intrinsic value of the platform increases the more it is used.

Each ecosystem participant brings their own strengths and attributes. In this networked environment, a robust coalition of private enterprise, government, regulators and customers as co-creators can tackle far more ambitious initiatives than if one party were to try to manage the endeavour by themselves.

Variables such as geography, regulation and salary arbitrage may result in sub-ecosystems, each optimised for its time and situation, but this is positive.

Governance

New operating models usually require new governance and the digital platform model is no different. As organisations transition from top-down, hierarchical models of management to cross-functional, customer-centric ways of working, the vertical command-and-control method must be replaced by a peer-to-peer, value-led trust-and-inspire method of working.

The sheer amount of data, and our ability to extract information, knowledge and insight from it require new governance solutions, and a new level of trust between providers and their customers, and/or between citizens and their government.

Outcomes and behaviours moderated by the many of a connected community will replace the autocratic, if well intentioned, decisions of the few.

Costs and profit

Industrial-era companies had high fixed costs and low marginal costs, had competitors who looked like they did, would increase volume and lower prices in response to well-known triggers, and were driven by supply economies of scale.

Internet-era organisations have low fixed costs (a small number of staff for the revenue realised) and no marginal costs - they don't create their own content, own their own hotel rooms or lease their own cars for use as taxis. It is the organisation's clients who create value for their customers. This network effect attracts more users, which creates more value, and so on. Scale is based on demand.

Creating a platform requires that the question of 'how does it make money' is replaced by the question 'how does it deliver value'.

If there is no value created, then there is no money to share.

Monetisation can arise from the transactional sale of the product or service itself, if that service is on-platform, or an access fee if the purchase decision is made on-platform, but the actual sale is conducted off-platform.

Further monetisation opportunities arise from insights arising from aggregated data, or advertising to those who use the platform.

What is a Platform?

The largest companies in the world are now mainly technology companies, and ecosystem companies. The question for many organisations is how to they embrace data and digital mindsets and pivot towards being, essentially, a tech company by reinventing their core business around data and digital. What will distinguish them is that their technology will bestow agility - it will allow them to move at speed and at greater scale than their competitors. For these companies, technology is not something that gets in the way, but is a means of continuous innovation and adaptation, and the key to involving others.

Platforms are a way of architecting technology components, so that logically grouped activities sitting on appropriate technology deliver a specific business goal as a standalone service, created and supported by a cross-functional team with responsibility for its effective operation and its iterative improvement. Each of these services is complete in itself, but when linked to other services becomes part of the capability of the company.

Each service may be changed, tested and put into production very frequently, and, just as important, if the changes don't improve customer outcomes, then they can be rolled back. This gives companies the agility they need to rapidly respond to constant competition and change. Because each component is self-contained (in terms of its building blocks and resources), other teams in the organisation are unlikely to have a detrimental effect on each other's services, something not possible with legacy monolithic products.

Within new governance, it also allows external parties to integrate their own services into the architecture, via application programming interfaces (APIs) to either extend core capability or to create new possibilities. Technology becomes an advantage, not a burden.

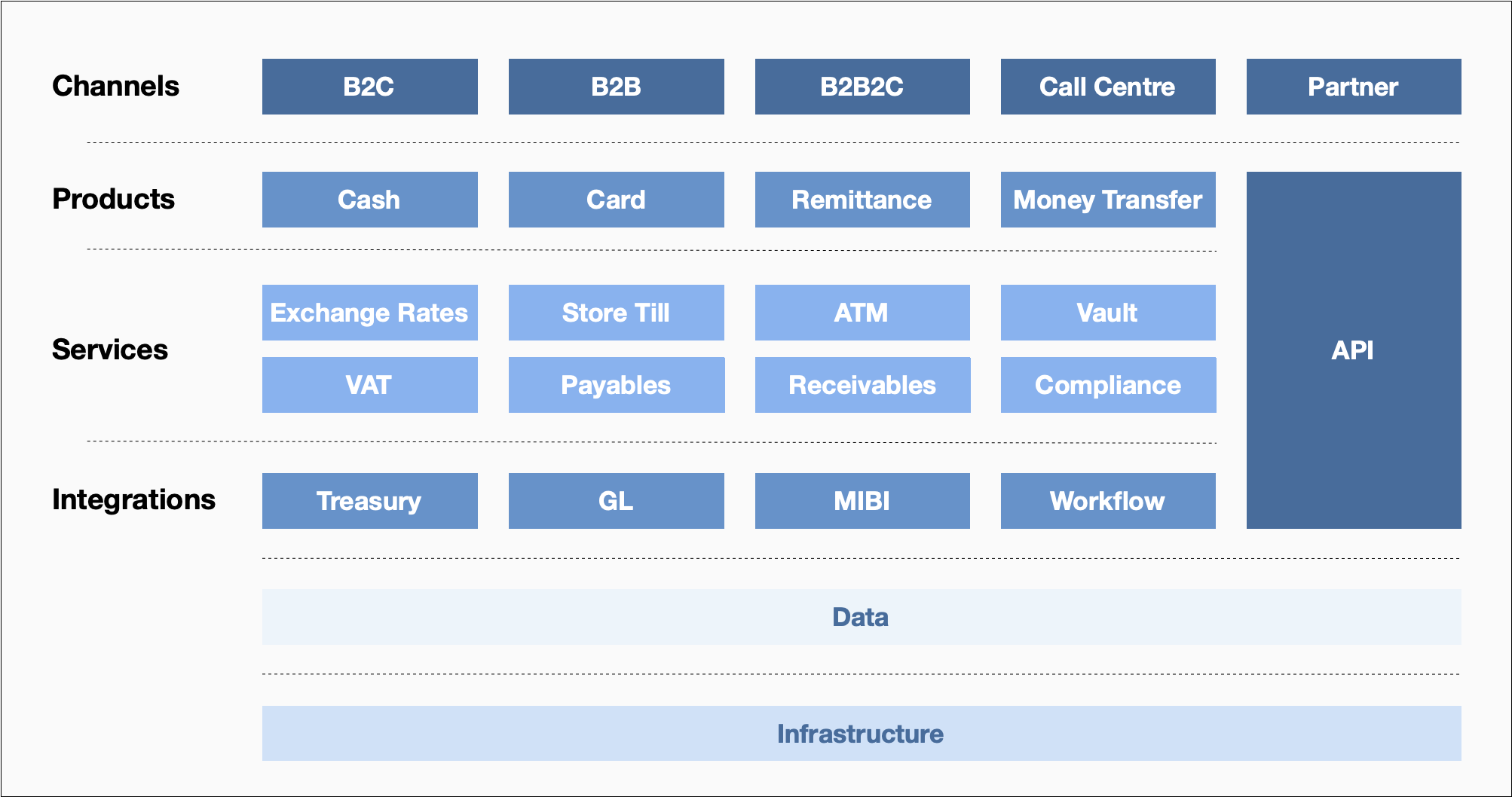

In the example graphic below, different organisational teams are each responsible for the reliable operation of a Service, and those Services are used to create the different Products provided to end-customers via different Channels. Partners can create new channels to market or enhanced products by using the APIs to access the various components needed. Because each component has a very clear business purpose and un-coupled technology, each is readily understood, used and amended - the epitome of corporate agility.

Platform architecture must be carefully considered, so that it best serves its ecosystem members. Too tight a control reduces the ability for third-parties to add new value. Being too open can bring challenges in steering the community, and in monetising their involvement.

Starting with a few key partners, who extend useful functionality in new ways, will best inform how to open up further over time. Any third-party will need reassurance that the value that they provide will be suitably rewarded. Some rules will be needed on who may participate, how value is recognised and how conflict is resolved.

Executive unease with ecosystems

Leaders used to managing in a top-down manner can find it very hard to embrace digital platforms and ecosystems. Many are hard-wired to protect their hard-won market share, and don't usually want to switch to growing the market. And to add to the challenge, ROI concerns and risk aversion sets short-termism against an openness to explore new opportunity.

Leaders who have spent much of their career controlling their hierarchical resources must now transition to orchestrating the company's cross-functional workforce, and the resources that their partners in the ecosystem will volunteer. This requires a very different personal capability, which some individuals may not be capable of acquiring.

Nevertheless, leaders are entitled to ask:

- How would an ecosystem resolve a customer's pain point any better than what we have now?

- What role should leadership play in our ecosystem? How will we govern it?

- What data and analytics are needed, to both serve the customer, and to provide the governance needed to make the ecosystem work?

- How would an ecosystem help us meet our strategic objectives?

- Is our competition providing an ecosystem already? If so, should we create our own, or join theirs?

Transparent discussion amongst the senior leadership team will help settle nerves and make any decisions made well-founded. Like any major transformation, creating a Platform as well as Products should only be embarked upon, if and when the reasons for possible failure have been acknowledged.

How a Platform contributes to corporate success

Success is no longer defined by an ability to scale, but by the corporate ability to learn (and unlearn) more rapidly.

The legacy model of stability - change - new stability is being replaced by the need for a state of continual evolution, in order to stay relevant as markets, consumer preference and technology evolve.

This requires a trade-off between the corporate ability to learn and its operational efficiency.

A company is not able to learn fast enough if it limits itself to the people within that single organisation, irrespective of how clever the individuals, or how many there of them.

It may be that a fundamentally different kind of organisation is needed in order to manage the constraints of learning vs operating, and to be able to tap into external knowledge and then apply it - especially in rapidly evolving circumstances.

Building relationships beyond the core organisation is a powerful way to access diverse knowledge. Every company has its supply chain of the many suppliers it uses to deliver value to the market. It may even include end-customers to provide feedback loops.

But organisations can view these third-parties simply as adjuncts to their own success, always looking to enhance their leverage to gain a better price, higher quality or consistent supply; in short looking for efficiencies across the operating model, ready to switch supplier if a better option is found.

This type of commercial association has had its place, but it does not build the type of partner relationship needed to benefit from working together when the market moves or greater productivity is demanded. Further, it often removes easy access to the tacit knowledge that is created through recent experience, and which has not yet been assimilated into the corporate knowledge bank.

Rather than shrinking commercial operations in the pursuit of business efficiency through a short-term transactional perspective, now is the time to build a new business operating model, a digital Platform that embraces the diverse nature of the whole supply-chain ecosystem and locks in the ability to learn from every different perspective.